Injuries Get Around Fast These Days

08.14.2017

What a horror, to see one of the best players in the game go tumbling past the base path, clutching his knee in pain and fear. I got to thinking about other horrors I have witnessed in decades of covering sports -- leaving the Real World, the coal-mine disasters, the murders, the tornadoes, the sieges, the police funerals I covered, out of this discussion. I’ve seen athletes careening into walls, into each other, joints going out of place.

On the very same day as Harper’s injury, Usain Bolt, in his last freaking race, blew up on the track, the image captured from head-on as he tried to slow down the human projectile of his own body – a now-retired athlete, hobbling off into the future, like so many athletes.

As I write this a few days later, in mid-August, the news from the Washington Nationals is that Harper’s knee is not broken or torn, but it is hyperextended and bruised, and he might even play again this season. By now, you will have read recriminations over the front-office decisions that led to a late and wet start of the game.

In the moments after it happened, the Mets broadcasters expressed their great respect for Harper, who plays in the same division. They see his blend of power and speed and ego 18 times a season.

My first mental association with Harper’s graphic stumble was with another gruesome accident in the District of Columbia. I was in RFK Stadium on a Monday evening in 1985 when Lawrence Taylor tackled Joe Theismann on a broken flea-flicker play near midfield and he and Jim Burt immediately began waving frantically for the medics to attend to Theismann. LT was one of the most fearsome defenders of any era, who used to brag about inflicting pain on opponents, but he stayed with Theismann for a long time. Theismann never played again after that broken leg; he never blamed LT, either.

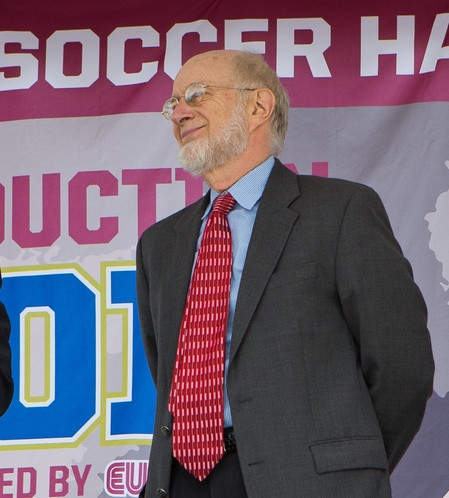

We’re all beginning to get a grip on what the normal violence of football does to the human body, including the brain. Harry Carson, who had the first hit on Theismann on that trick play, talks about having slower speech since his playing days but he remains a thoughtful, active citizen, thank goodness. He’s one of the lucky ones.

With players in mid-career, like John Urschel of the Ravens, starting to quit to save their brains, even the people who run the National Football League are beginning to get a glimmer of a clue about the damage to most people who have played this dangerous sport.

That is a huge advance. The damage to football players is beginning to add up. John Mackey, whom I covered in high school, was a great tight end and a union leader but ultimately his wife, the stalwart Sylvia Mackey, could not control this huge man any better than defensive players could, and he passed in a home. Dave Duerson, bright and personable, shot himself in the chest, to preserve his brain for the evidence that added to the understanding of the game-by-game brutality to the brain, taking place right now, at a stadium near you.

But every sport has its injuries, its accumulated trauma. Michelle Akers, a gentle soul and the most formidable female soccer player I have ever seen – Big Bird on a mission -- played the 1999 Women’s World Cup, despite a diagnosis of fatigue syndrome. “Michelle adheres to the Joe Frazier school of defense, always leading with her face,” my colleague Jeré Longman wrote. She played in a haze into the 91st minute of the final – and survived to go home to her horse farm.

Then, of course, there is the legend of Mickey Mantle. Catchers I knew in the ‘60’s said they hated to hear Mantle grunt in pain from planting his right knee, wounded in the 1951 World Series. Mantle had other injuries: I was in Baltimore one night in the early 60s, one of my first road trips for Newsday, when Mantle tried to catch a ball near the chain-link fence in Memorial Stadium, and his spikes got caught, and he broke his foot. I remember him, pasty-white, on crutches, leaving the clubhouse for the hospital, as we reporters stood in the doorway. He smiled wanly and said, “See y‘all.”

I wasn’t in Yankee Stadium the night Mantle hustled down the line with all his sprinter/running back speed, only to have his hamstring pop, and he tumbled to the ground. As I recall, Leonard Shecter of the New York Post described Mantle as resembling a deer being shot in mid-stride.

But I was sitting on the bench with the Hofstra baseball team in 1958, as the student publicist, when my friend Jerry Rosenthal got hit alongside his left eye, by a fastball from a St. John’s pitcher. As they carted Jerry to the hospital, we all thought about Herb Score getting hit in the face by a line drive the year before.

When he got out of the hospital, Jerry forced himself to play in a summer league – and become an all-conference shortstop for Hofstra, and later a minor-leaguer; I love his stories of teammates like Rico Carty and Bill Robinson and Pat Jordan. Jerry was still playing in a hardball league heading into his 70s; I would not have bet on it, the day he crumpled at home plate.

Jerry had guts, like Bernard King rehabbing his knee and finally coming back, or great prospects like Don Mattingly, Tony Oliva and my Brooklyn friend Tommy Davis, who had great careers but fell short of Hall of Fame levels because of injuries.

I won’t even segue into my normal abolitionist rap about boxing. I’ve seen too many people I admired – Alexis Argüello, Riddick Bowe, Muhammad Ali, Smokin’ Joe Frazier – wind up impacted by the brain-battering essence of that “sport.”

I even knew one athlete who died during a game. Flo Hyman, 6 feet, 5 inches tall, charismatic and intelligent, made women’s volleyball my favorite event at the 1984 Olympics. Nobody realized she had Marfan syndrome, until her heart stopped during a professional game in Japan in 1987. The Women’s Sports Foundation named its annual sportsmanship award for her.

Injuries transcend team loyalties – hence, the fairly universal applause for a wounded athlete, even a brash and talented tormentor like Bryce Harper. Writing in the middle of August, I can only wish Harper a speedy recovery (but take it easy on my Mets, dude.)

###

George Vecsey was a sports columnist for The New York Times

from 1982 through 2011. He’s reachable at: vecsey@nytimes.com.