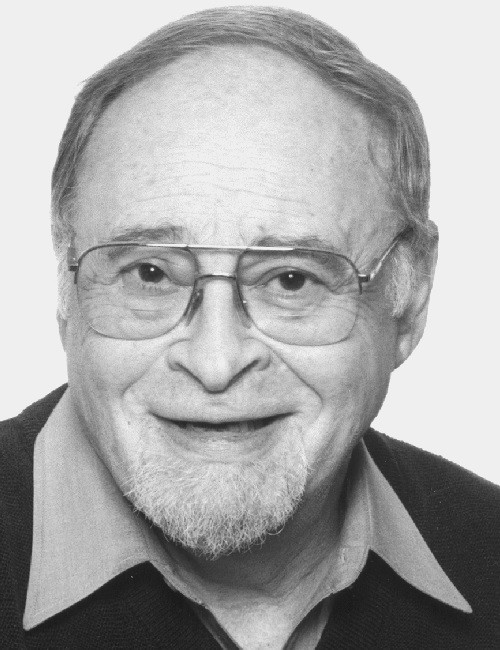

Jerry Izenberg Remembers NSMA Hall of Famer Sam Lacy

02.24.2017

He never cared much for the new computer technology, and, as he aged, acute arthritis came between him and his typewriter. Because of this last, for the last 30 years of life, Sam wrote his weekly sports column for the Baltimore-based Afro-American in longhand on a plain paper tablet.

But sing no sad songs for the man whose career began when neither black players nor black writers were welcome in segregated major league baseball and ended shortly before his death at age 94 with his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame’s writer wing.

Now the National Sports Media Association (formerly known as the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association) will induct him into its Hall of Fame. Sam never sought awards but this is a good thing for the rest of us because in our business what Sam did and what he stood for was all about what we are supposed to be.

Both his life and his legacy were a kind of autumn wine, aged in the vineyards of a social change he helped to create and selflessly triumphant in a way that has kept him true to both himself and his readers.

This was no small achievement. In all honesty, sportswriters work for the toy department of the American newspaper and we tend to overrate the significance of what we do. Generally, all that we do is to breathe an extended life into the mornings-after of what essentially remain the games of little boys and girls, now played for staggering sums of money by grown men and women. Sometimes, in the telling of it, we forget that opening a debate over the distance of the NBA's 3-point line is not exactly give-me-liberty-or-give-me-death material.

While we write about what we think of as history, Mr. Lacy helped create the history about which he wrote. What he did was to tell his readers what otherwise might have remained a lot of silent truth and placed it in perspective with a gift of insight that belies rebuttal. In the pursuit of that truth, he never pandered to anyone else's idea--establishment or rebel--of what was right.

His readers were primarily African-Americans, which is the rest of the country's loss. Even for them, he was not always been politically correct. He had little tolerance for charades. Like it or not - and most of them did - he remains a mirror to the American reality, the journalistic eyes and ears of that community, providing a viewpoint it rarely got anywhere else.

Conversely, for the white community--and, yes, at times, the black—he was the conscience that never spoke to them. They may not have wanted want to hear it but are better off for having heard it. For more than six decades, he was America's version of Diogenes with a deadline. It was only natural that it would be Sam Lacy, who would become a critical cog in the shattering of baseball’s shameful whites-only charade. He was there when Joe Louis and Jesse Owens rose above America's color prejudice inside the arena and was privy to the burdens American social mores would not remove from them outside of it.

He was there as a major force when Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby waged their lonely battles to shatter the game’s color line only to discover he was just as isolated in his attempts to cover them from the press box. Long before it happened, Lacy was the heavy artillery of this struggle. “I thought the way to do it was to embarrass them in the public print," he told me. He asked Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the commissioner of this lily white baseball world, for just 10 minutes "anywhere, any time, any place" to prove his case. He never even got an answer.

But he wrote -- and people read. He spoke -- and people heard. Landis’ office “appointed’’ him to a committee to study integration. The committee never met. But Mr. Lacy never backed down. Eventually, it was Branch Rickey who told him it would get done. “He became my hero," Sam said, "because he braved the wrath of owners. He went out and did it. Now Bill Veeck, you never knew what he meant. I mean, he didn't sign Larry (Doby) until well after Branch Rickey signed Jackie." When the walls came tumbling down, as isolated as things got for both Robinson and Doby, that's how isolated it got for Sam Lacy.

In 1948, he became the first black journalist to be accepted into the Baseball Writers Association of America. The BBWA card is the "open sesame" to all ballparks, press boxes and training camps. That's what it says, but as they used to sing along Catfish Row, "It ain't necessarily so."

This is the way it was for Sam Lacy. In Cincinnati, the local BBWA press box custodian stood in the doorway in a more than symbolic gesture that seemed to say "not on my block." “I have a BBWA card, " Lacy said, with firm politeness. “I don't care." “I need a place to work," Lacy said in a level, determined voice. So the guy called security and they put him in a box seat on the first base line with a rope around the box. “Nobody else could come in," Lacy recalled, and then he laughed and added, "was that reverse discrimination?"

At the entrance to Yankee Stadium, a gatekeeper saw his card and challenged him: “Whose card is this? Where did you get it? You aren't getting in here." “Milt Richman of the United Press came along and he told the guy to get out of the way and he walked Lacy in." At Pelican Field in New Orleans, the Indians were playing an exhibition game. There were two African-Americans involved -- Larry Doby on the field and Sam Lacy on the roof. His entry to the press box was barred. "Don't show me that card," the jerk said. "It ain't no good here." “I have to work, "Lacy said. “That ain't my problem. Take a chair and go up on the roof for all I care, but you ain't comin' in here." “So I did. I got my chair and went up on the roof. The next thing I know here came Dick Young (New York Daily News), Roscoe McGowen (New York Times) and Bill Roeder (World Telegram and Sun) and they're each carrying a chair." “What's going on?” I asked. “We need to get some sun," Young said. “Those fellows had been down at spring training for six weeks in Florida. They didn't need sun. They just stood up for a principle.’’

Standing up for principles in print is something that Mr. Lacy knew about in journalism and in the streets. For 62 years his was an idyllic marriage with Barbara Lacy, an extremely fair-skinned Afro-American. There came a time when he went down to a local Baltimore mosque of the Nation of Islam to present an award to Muhammad Ali. An argumentative Fruit of Islam security guard told him he was welcome but not his "white" wife. Mr. Lacy did not explain that she wasn’t white. He didn’t say she was his wife. He left the award on the temple steps and he and Barbara went home.

The story was the punctuation mark to his explanation of how trivial this whole race thing can get. He never left his focus on the important things ... on right and wrong ... on telling his readers what he believed and why he believed it. Before his Cooperstown induction, he told me. Listen:

The old baseball color line: "It cheated everyone ... the fans, both black and white, who never got to see those great players ... the Negro League players because of the obvious denial involved ... the white players because they never got to measure themselves against some of the greatest players who ever lived."

Today's athletes: "Don't even ask me that. These fellows used to play for the fun of the game and to represent a team. Nowadays, they're mercenaries, worse than mercenaries. For one more dollar they go across the street to play. And I am disgusted by all those gyrations after they make a tackle, the way they mug for the camera. We never got that from Oscar Robertson, Dr. J. or Gale Sayers."

The loss of tradition: "I couldn't believe it when Tim Raines said he had never heard of Jackie (Robinson) until he got to the majors and the others who said they didn't care. It's so sad because they never heard of George Washington Carver and one day one of them will say he never heard of Martin Luther King. It's not about what once were negatives. It's about knowing where we came from."

Awards and honors: "The Society of Black Journalists honored me because they said I was the one who opened the door. I don't see it that way. I told them I didn't deserve it because it doesn't mean anything to open a door if nobody comes through it. They came through. That's what matters."

Perhaps. But they had one hell of a door-opener.

###